And the old city.

The Oude Kerk was built from 1300 through the 1460s. The Calvinist iconoclast rampages of 1566 led to the destruction of the church's altars and its sculptures of saints.

The view of the nave, from the choir.

The figures on the misericords of the choir stalls wear clothing styles from 1480, so it is thought that they were carved that year.

The ceiling.

The great wood pipe organ was completed by Christian Vater, in 1726.

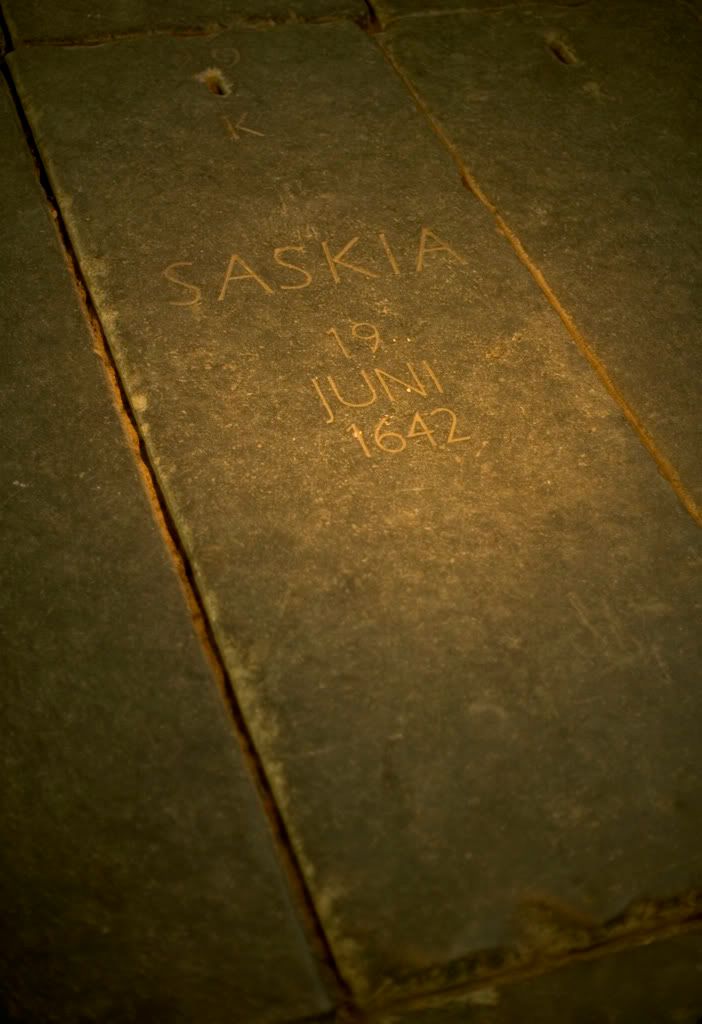

Rembrandt's wife Saskia was buried here. They already had lost three of their four children, at very young ages, and the artist was devastated then to lose his wife.

The Royal Palace and the Nieuwkerk.

The Nieuwkerk was closed for restoration work, so this is all we saw.

The Rembrandthuis was the home and studio of the great artist, from 1639 to 1658, at which point his dire financial state forced him to leave. It also includes a fine collection of his brilliant etchings.

The kitchen.

Many of his greatest pieces were painted in this studio. His assistants prepared his paints and canvases, and the room was filled with various objects which he would incorporate into his works.

Not far from the Rembrandthuis is the Nieuwmarkt.

The Waag was built as a city gate in 1488, but became the Weighing House in 1614. It now houses a restaurant.

By the Seventeenth Century, the triumph of Protestantism had liberated Dutch artists from Catholic Church strictures on subject and style, although the iconoclast movement reversed the dogma, at times forbidding depiction of many religious subjects. But this meant a flowering of the exploration of secular matters, and because every wealthy Dutch family wanted itself immortalized on canvas, Dutch financial prosperity saw a proliferation of artists and artistic schools.

If the Renaissance had been largely about the discovery and perfection of the depiction of visual realism, such realism largely had been depicted in stasis, or near stasis. There was little attempt to show these perfected forms in movement. With Seventeenth Century Baroque art, and at times to great excess, visual realism came alive and took flight. In Protestant Holland, however, such depictions of movement remained relatively subtle and restrained, and Dutch art is all the more gracious for it. You would have to move south, to Belgium, to see the tumbling, twining, twisting forms of Rubens and his followers.

The Baroque also was about explorations of the play of light, and the Dutch, more than anyone, took Caravaggio's revolution and mastered it. The Rijksmuseum is one of the world's finest, and among its many treasures are numerous Baroque masterpieces.

Among the great works in the museum is the 1628-1630 The Merry Drinker (or Jolly Toper), by Frans Hals, the great portraitist of middle class Haarlem. Hals uses an almost impressionistic technique to create a visceral sense of the man's teetering drunkenness.

H.W. Janson:

Everything here conveys complete spontaneity: the twinkling eyes and half-open mouth, the raised hand, the teetering wineglass, and-- most important of all-- the quick way of setting down the forms. Hals works in dashing brushstrokes, each so clearly visible as a separate entity that we can almost count the total number of "touches." With this open, split-second technique, the completed picture has the immediacy of a sketch. The impression of a race against time is, of course, deceptive. Hals spent hours, not minutes, on this lifesize canvas, but he maintains the illusion of having done it all in the wink of an eye.The Rembrandt collection includes the Landscape With A Stone Bridge, and some of his most famous works, including what many consider to be his masterpiece, The Night Watch.

Janson:

His famous group portrait known as The Night Watch, painted in 1642, shows a military company assembling for the visit of Marie de' Medici to Amsterdam. Although its members had each contributed towards the cost of the huge canvas (originally it was even larger), Rembrandt did not give them equal weight. He was anxious to avoid the mechanically regular designs that afflicted earlier group portraits--a problem only Frans Hals had overcome successfully. Instead, he made the portrait a virtuoso performance of Baroque movement and lighting, which captures the excitement of the moment and lends the scene unprecedented drama. Thus some of the figures were plunged into shadows, while others were hidden by overlapping. Legend has it that the people whose portraits he had obscured were dissatisfied. There is no evidence that they were. On the contrary, we know that the painting was much admired in its time.Other works include a contrasting pair of self-portraits, the first from 1628, and the second from 1661. Rembrandt often painted himself, and it often was because he couldn't afford to pay a model. His self-portraits are brutally honest, with no attempt at vainglory. They also reveal why I consider him to be one of the handful of greatest ever artists: his humanity. It's not only that he depicted people with such intense tenderness, but that he captured their souls with an almost supernatural vitality. When you look into the eyes of one of Rembrandt's portraits, you feel that you are looking into a living, breathing being.

Also in the museum is another great group portrait, from 1662.

Helen Gardner:

In Syndics of the Cloth Guild, representing an archetypal image of the new businessmen, Rembrandt applied all that he knew of the dynamics and psychology of light, the visual suggestion of time, and the art of pose and facial expression. The syndics, or board of directors, are going over the books of the corporation. It would appear that someone has entered the room and they are just at the moment of becoming aware of him, each head turning in his direction. Rembrandt gives us the lively reality of a business conference as it is interrupted; yet he renders each portrait with equal care and with a studied attention to personality that one would expect to be possible only from a long studio sitting for each man. Although we do not know how Rembrandt proceeded, this harmonizing of the instantaneous action with the permanent likeness seems a work of superb stage direction that must have needed long rehearsal. The astonishing harmonics of light, color, movement, time, and pose have few rivals in the history of painting.One of my favorites, because it so typifies Rembrandt's sense of humanity, is the sweetly tender and loving 1667 The Jewish Bride.

The Vermeer collection includes the masterful 1657-1658 The Little Street, the layered planes so typical of Vermeer, and of his influence on later Dutch artists, right up to the abstractions of Piet Mondrian. But Vermeer's genius was in capturing moments of such solitude and intimacy that the viewer almost feels like an intruding voyeur. Superb examples from the museum are the 1658 The Milkmaid, the 1663-1664 Woman In Blue Reading A Letter, and the 1667-1668 The Love Letter.

Janson:

The carefully "staged" entrance serves to establish our relation to the scene. We are more than privileged bystanders: we become the bearer of the letter that has just been delivered to the young woman.But what is the meaning of their expressions. The maid seems almost amused, the recipient surprised, perhaps even a little afraid. We are shown the mystery, but not invited in.

As usual with Vermeer, however, the picture refuses to yield a final answer, since the artist has concentrated on the moment before the letter is opened.But Vermeer also was revolutionary and brilliant in his technique, and as was the case with most Baroque painters, he was enchanted by the dance of light. This painting, too, reveals Vermeer's fascination with layered planes.

Vermeer's real interest centers on the role of light in creating the visible world. The cool, clear daylight that filters in from the left is the only active element, working its miracles upon all the objects in its path. As we look at The Letter, we feel as if a veil had been pulled from our eyes, for the everyday world shines with jewellike freshness, beautiful as we have never seen it before. No painter since Jan van Eyck saw as intensely as this. But Vermeer, unlike his predescessors, perceive reality as a mosaic of colored surfaces-- or perhaps more accurately, he translates reality into a mosaic as he puts it on canvas. We see The Letter not only as a perspective "window," but as a plane, a "field" composed of smaller fields. Rectangles predominate, carefully aligned with the picture surface, and there are no "holes," no unidentified empty space.The Van Gogh Museum collection consists mostly of the paintings Vincent Van Gogh gave to his beloved brother and benefactor, Theo.

The permanent collection includes Vincent's first great masterpiece, the 1885 The Potato Eaters.

Janson:

Van Gogh, the first great Dutch master since the seventeenth century, did not become an artist until 1880; as he died only ten years later, his career was even briefer than Seurat's. His early interests were in literature and religion. Profoundly dissatisfied with the values of industrial society and imbued with a strong sense of mission, he worked for a while as a lay preacher among poverty-stricken coal miners in Belgium. This same intense feeling for the poor dominates the paintings of his pre-Impressionistic period, 1880-1885. In The Potato Eaters, the last and most ambitious work of those years, there remains a naive clumsiness that comes from his lack of conventional training, but this only adds to the expressive power of his style.The stark unbeautified characters already reveal Van Gogh's sensitivity to depicting things as they were, not as we would like them to be. The precognitive visualness of the Impressionists would be a natural fit. So would their brilliant colors.

When he painted The Potato Eaters, Van Gogh had not yet discovered the importance of color. A year later, in Paris, where his brother Theo had a gallery devoted to modern art, he met Degas, Seurat, and other leading French artists. Their effect on him was electrifying. His pictures now blazed with color, and he even experimented briefly with the Divisionist technique of Seurat. This Impressionist phase, however, lasted less than two years. Although it was vitally important for his development, he had to integrate it with the style of his earlier years before his genius could fully unfold. Paris has opened his eyes to the sensuous beauty of the visible world and had taught him the pictorial language of the color patch, but painting continued to be nevertheless a vessel for his personal emotions. To investigate this spiritual reality with the new means at his command, he went to Arles, in the south of France. It was there, between 1888 and 1890, that he produced his greatest pictures.My photo blog of Van Gogh's years in southern France can be found here.

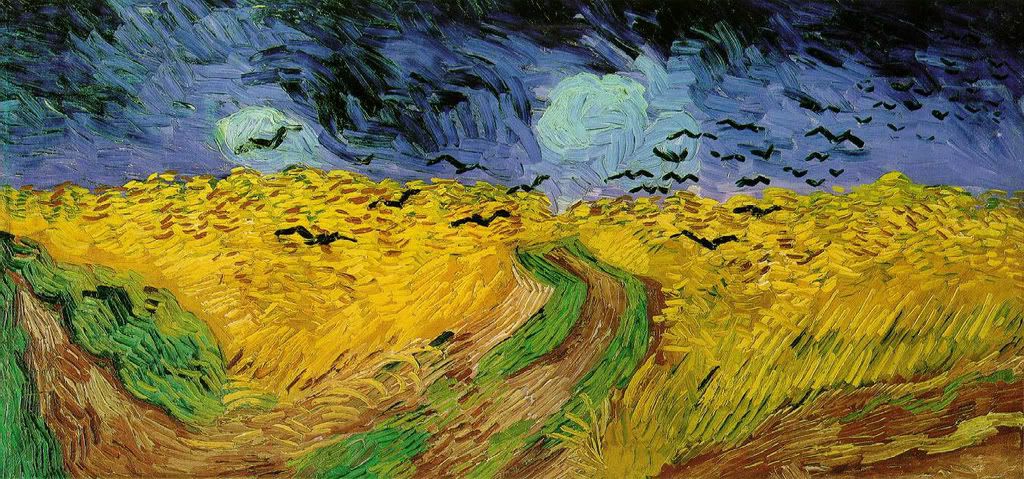

Works from this period, now in the Van Gogh museum, include the 1888 Yellow House, his home in Arles; the 1890 Irises and Almond Blossoms; and the haunting 1890 Wheatfield With Crows, which was painted the month of the artist's suicide, and which reveals a psyche now so fractured that the usual tight imagery is literally breaking apart.

We've been to the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and to Terezin and Auschwitz, but there is something particularly powerful about the human scale of the Anne Frankhuis. When you walk up the narrow stairs, it hits you in the gut that this small group of people walked these same steps to their years of necessary self-imprisonment, and were forced to walk back down them, on their way to their eventual murders.

And back outside.

It's considered uncool to take photos of the Red Light district, but here are some of Amsterdam's other pop culture attractions...

No comments:

Post a Comment